By KEN KORCZAK

Today I divert briefly from UFOs & the Paranormal to offer my commentary and analysis of Prof. Kenneth Vickers’s massive 773-page study of Humphrey, The 1st Duke of Gloucester

It’s been 600 years since he was born and lived. To study his role in history, scholars must tirelessly comb through the brittle, yellowed pages of antiquity where and if they can be found in cramped boxes and obscure storage shelves in the basements of various British institutions.

Was “The Good Duke” or one of the most despicable violent, lecherous figures in English history, a man who singlehandedly did more to bring The Renaissance to “The Sceptered Isle” –or a combination thereof?

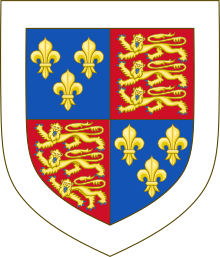

Humphrey, the Duke of Gloucester, was the youngest son of King Henry IV, and the ever-loyal brother and lieutenant of Henry V. Born in 1390 and died in 1447, Humphrey remains among the most confounding and enigmatic personalities to stride across the stage of history.

Pinning down the essential nature of The Duke is a task of monumental difficulty. That’s what makes this 773-page exhaustive study of Humphrey by British Prof. Kenneth H. Vickers (1881-1958) an extraordinary academic achievement.

Vickers gave it his all. He vigorously attacks the problem of defining Humphrey page after painstaking page. He provides a voluminous bibliography of cited sources that is almost half as long as the text itself. A muscular appendix expands on a multitude of additional issues.

Vickers’ conclusion? Duke Humphrey probably deserves his lasting reputation as “The Good Duke,” among certain segments of English society, high and low. However, the greater measure of the man is represented by his numerous, sometimes shocking failings.

VIRULENT NARACISSM, GREED AND LECHERY

Duke Humphrey was greedy, power-mad and an egomaniac. His lusts for fame and wealth were without limit. He could be cruel and wildly impetuous, but also witty, personable and charming. He was brilliant — yet completely unable to sustain a long-term effort — be it in war, politics or devotion to a single woman. He lived to be flattered and adored by his court of groveling sycophants; his sexual hunger for the opposite sex is legendary.

Yet, Vickers manages to uncover Duke Humphrey’s saving grace: His burning love of literature and learning. Despite his repugnant character flaws, Vickers credits Humphrey with nothing less than bringing the Renaissance to England and delivering his country from the cloying cobwebs of the Dark Ages. If it wasn’t for Duke Humphrey, Vickers says, England may have remained mired in colloquial ignorance for decades to come.

Humphrey single-handedly thrust England out of darkness and into the light by his aggressive sponsorship of Italian intellectuals. Somewhere along the line, Humphrey developed an insatiable love of the ancient Greek and Roman texts that were exploding on the scene after being lost for centuries in medieval anti-intellectualism.

At great personal financial cost, Humphrey commissioned a small army of brilliant Italian writers and linguists to translate into Latin, French and English the works of Plato, Virgil, Cicero, Marcus Aurelius, Lucretius and dozens of others. These translations were sent by the hundreds to Humphrey in England where he read them with great relish — but then he breathed new life into the local academic community by donating hundreds of volumes to what had become a backward, calcified and stagnant Oxford University — the primary body of learning on the British Isles.

Today it might seem difficult to comprehend that the donation of a few hundred books could be an act of real significance; however, the printing press was still a few decades away. Books were hand-made and hand-lettered by scribes. The production of a single book involved hundreds of man-hours — and those who were literate enough to do the job were rare members of society indeed. Thus, books were objects of rarity and enormous value.

“THE GOOD DUKE”

Also, consider that no one — perhaps not so much as a single person –- in England was capable of reading — not to mention translating — ancient classical Greek. For this, Duke Humphrey had to rely on the distant Humanist scholars of Italy. Merely the logistics of finding them, contacting them, making deals with them and arranging for translated books to be shipped to England was a remarkable undertaking. No one else was interested in doing it. It was Duke Humphrey who made it happen.

The historic effect of this effort is still rippling through British society today, Vickers claims (keeping in mind this manuscript was first published in 1907). Thus, it would be impossible to overestimate the service The Good Duke paid to all of Britain. But, ah, alas, despite this priceless everlasting boon bequeathed upon “Old Blighty” by the hand of Humphrey, the rotting stench which clings to his reputation can never be scrubbed clean — nor should it be.

WAR IN FRANCE AND THE HAINAULT DISASTER

It was his lifelong, undying and illogical support of his brother’s war with France, especially after it was hopelessly and utterly lost, which brought untold tragedy to both realms, not the least of which is the unimaginable suffering inflicted upon countless thousands of peasants eking out a living in the French countryside.

If this wasn’t enough, Duke Humphrey’s fantastically insane decision to march an English army to Hainault (or Hainaut) after his semi-legitimate marriage to Jacqueline, Countess of Holland, so that he could claim what he deemed to be his — represents one of the most egregiously rash and ill-advised military blunders of all time. This action also unleashed monstrous cruelties of war upon a land of dynamic, innocent, peaceful people who wanted nothing of England but to be left alone.

It was all so unnecessary!

The Hainault campaign drained vast sums of treasure from the English coffers, wreaked hideous brutalities upon the prosperous people of The Low Countries– raping, pillaging, killing, burning, ravaging, destruction of cattle and crops — all for the insipid whims and greed of Humphrey!

Today’s historians owe an enormous debt to Professor Kenneth Hotham Vickers for this extraordinary manuscript. Before Vickers brought out this volume more than a century ago, there was a yawning gap in the modern record. The life and deeds of one of England’s most prominent princes were languishing in the obscurity of dusty archives.

Kenneth Hotham Vickers graduated from Exeter College, Oxford, in 1904. He later lectured at University College, Bristol. In 1922, he became Principal of the University College of Southampton, a position he maintained until his retirement in 1946. He should be remembered for this great work of history that serves as an exceptional legacy for a man who devoted his life to education and scholarship.

NOTE: For more stories of historical significance, please see: KEN-ON-MEDIUM.