By KEN KORCZAK

By KEN KORCZAK

A novel that’s like a slow IV drip of misery into your veins, and yet, it inspires and hints at deeper mystical wonders

Author Fergus MacRoich has crafted a remarkable piece of literature that can be read and interpreted on many levels because of the multi-tiered stratum of meaning he built into the narrative.

On the outside, this novel would appear to be a tale of gritty and brutal realism featuring a supremely unfortunate child born to a black heroin-addict mother living a life of deplorable squalor in some stark flophouse.

However, the realism of the narrative is undermined by mystical elements that dance just around the edges, although the latter might be invisible to the casual reader.

Before I go further, I should first deal with the decision of Mr. MacRoich, who is white, to narrate his tale using what I’ll call the “Ebonic Voice” — that is, a mode of speech common to many black Americans. Here’s a sample from the book:

“Night was the worst for Ishmael. A baby, he couldn’t walk out of his crib. Go to the store and feed his own self. Had to lay in his crate. Waiting to be fed. But the woman in the other room didn’t have no milk. And Willy was gone. Maybe looking for a real cow. When he cried the woman slept right through.”

This might open the author up to charges of cultural appropriation. However, I would argue that this is not the case here. Rather, I cite a long-defined and accepted literary technique known as “The Uncle Charles Principle.” This is a technique originated by (or at least credited to) the great Irish writer James Joyce.

Using the Uncle Charles Principle, even when the author is writing from the omniscient point of view, he or she writes in a way that matches how a character might speak, act and think.

So, in this case, we have the viewpoint character, Ishmael, who naturally speaks and thinks in the Ebonic voice — yet the entire narrative reads “Ebonic” even when we are not inside the head of the character, such as when the author is describing what is happening to Ishmael.

Some might find it odd or wrenching that, even if an author is white, he is writing to portray the urban street cadence of a black man. But this is the Uncle Charles Principle at work, and it is a well-accepted literary technique.

The best-selling writer Cormac McCarthy, for example, is known to make frequent use of this approach.

BUT BACK TO OUR TALE …

I’ll warn you that if you’re looking for a “feel good” book to read on the beach, Fried Chicken, Jesus and Chocolate is not it. I found it difficult to enter the dark and desperate world of Ishmael. I hasten to add that this is what makes this book a powerful piece of writing. After all, the purpose of art is to make you feel something intensely, whether that something is joy, horror, wonder, despair, misery or delight.

‘Fried Chicken’ is not so much a painful punch in the gut, as it is a slow IV drip of syrupy misery pumped into your veins. Any caring human being with a soul (or a pulse) will be dragged to a dreary melancholy as he/she confronts poor baby Ishmael eating live cockroaches and flies to stave off starvation. He does that while wallowing in his urine and feces-packed diapers.

Baby Ishmael is ignored for hours or days on end as his heroin-dazed mother lies comatose in the next room on a pile of filthy newspapers. Pay special attention to the detail that a toddler-Ishmael also eats lead-tainted paint chips, a practice that has been associated with brain damage in children, especially children of poverty.

Ishmael’s only socialization comes from an erstwhile, yet kindly-boyfriend-heroin-supplier to his mother. He also is informed by watching violent-yet-loony cartoons featuring Wiley E. Coyote for hours on end. So desperate is Ishmael to make a deeper connection with some significant “Other” he adopts a spider in the window as his “mother,” and this connection becomes deep and psychological.

When circumstances eventually rescue Ishmael from his heroin den of desperation, it would be an understatement to say that here we now have a child shaped in a unique way to confront the “real world.” How will he manage? Can he ever thrive? Will he implode? Does he even have a chance?

MYSTICAL ELEMENTS

Now I want to briefly touch on the mystical elements of this story.

Overtly, Jesus and Biblical Scripture come to play a large role in Ishmael’s life after he is exposed to these elements by his grandmother. However, the “Jesus” imprinted on the perception of Ishmael is a surface-level figure of Christ based on an image— a poster of a “Black Jesus” in his grandmother’s house.

At the same time, Ishmael appears to develop a direct psychic connection with a Jesus that I would not call the “Mainstream American Jesus,” nor even a Gnostic Jesus, but a mystical, almost Hermetic kind of Jesus. And yet, this version of Christ is not averse to Old Testament habits. It admonishes his follower against gluttony and lust, even though Ishmael fairly starves throughout the book, and never comes close to “gettin’ any.”

Beyond this, I would argue that there is a far deeper and stronger mystical-spiritual element implied, and that involves the imagery of the spider. It can’t be an accident that Ishmael not only adopts a real spider as his first true “mother,” but comes to see his grandmother as a “Spider Woman.”

Ishmael’s first spate of trouble with authority comes after he violently beats a fellow student for killing a spider. As an anthropologist, mythologist or and folklorist might tell you, the spider motif, and especially the “Spider-As-Woman” is among the deepest and most ancient of our mythic archetypes.

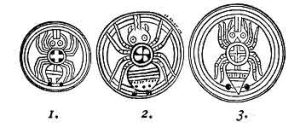

It’s found throughout an array of ancient cultures. Stylized spider depictions have appeared independently among diverse societies, even if they are separated by oceans and continents. Some suggest that one of the most ancient mystical “power symbols,” the swastika, has its origin/inspiration in the central element of a spider’s web design.

The spider is always a goddess figure. Some scholars say this explains why the crafts of spinning fabrics and weaving have always been the bailiwick of women. The spider woman-goddess — rooted in ancient times when all societies were matriarchal — is the primal architect of the Universe. Her spinning and weaving virtually knit reality together.

It’s as if Ishmael’s brutal upbringing (along with brain damage from eating lead-based paints and malnutrition) has severely suppressed his intellectual ability, but this in turn has allowed his psyche to have a direct penetration to a deeper well of ancient mystical knowledge and guidance.

The latter is symbolized by the ancient Spider-Woman-Goddess motif.

BUT THEN AGAIN …

It’s possible that I’m reading more into this than I should, but it hardly matters. Fried Chicken, Jesus and Chocolate is that kind of book. Again, it can be read on any level the reader chooses. None of those levels would be “wrong.”

The gritty realism is stark and obvious, but the abstract elements are there just below the surface — but sometimes not so hidden, in my view. (Note: I’m not even going to discuss the significance of the chicken and the chocolate. Why? Because I’ve blabbed on long enough!) It all makes this one of the most fascinating and vexing books I have read in some time.

It disturbs, beguiles and challenges.

It thrusts readers out of their comfort zone. Anyone not emotionally moved by this narrative would have to be psychologically numb, or dead.

NOTE: For more in-depth review of literature, please see KEN-ON-MEDIUM