By KEN KORCZAK

How failing bowling class in college led to my successful practice of remote viewing — but only after I threw out the CRV Manual and did it ‘my way.’

I first became aware of remote viewing in the 1980s.

What brought it to my attention was a 1981 Washington Post article written by then-hard-nosed Washington Post investigative journalist Jack Anderson.

Anderson was the first reporter to break the story about remote viewing, a program that was highly classified –- in fact, top secret. In his first article, Anderson expressed skepticism to the point of contempt and scorn, calling the Pentagon-sanctioned psychic spying effort “voodoo warfare.”

His column, “Pentagon Invades Buck Rogers Turf,” was riddled with contemptuous terms like “hogwash,” “futuristic fantasies” and “government Ouija board warriors.”

An old-school watchdog-style reporter eager to expose government corruption, Anderson believed he had rooted out an egregious example of outrageous government waste of taxpayer’s dollars. So, he continued to dig into the story, but four years later, Jack Anderson had already started to change his tune — at least a little.

Initially hoping to expose a multi-million government boondoggle, Anderson assigned a top member of his investigative team, Ron McRae — a former government “insider” recruited as a journalist — to conduct a deep dive into the remote viewing program.

This resulted in a book lead-authored by McRae with the help of Anderson’s well-cultured network of insider informers. It was titled:

“Mind Wars: The True Story of Government Research into the Potential of Psychic Weapons.”

“Mind Wars: The True Story of Government Research into the Potential of Psychic Weapons.”

This book piled on more ridicule by highlighting the weirder facets that occurred during the CIA-DIA remote viewing program — and let’s admit it, there was plenty of that.

However, the book also allowed the proponents of the program to make their case for its legitimacy fair & square.

McRae concluded by admitting the “possibility of something being real here.” And so, remote viewing eked out its first tiny measure of respectability.

I was a young 20-something newspaper reporter in 1984, and so I paid attention to Pulitzer Prize-winning muckrakers like Jack Anderson. I also read with fascination the ‘Mind Wars’ book researched by his investigative team.

Alas, a subsequent scarcity of information about RV through the 80s and the early 90s put the whole issue on the back burner for me. Then the government canceled the RV program in 1995. Not all, but a significant portion of the information relating to the effort was declassified shortly thereafter by the Clinton Administration.

SOME CASHED IN

Unfortunately, one outcome of that was that some of the “third-eye spies” who were among the first RV recruits and practitioners were now free to write books and become public celebrities. Two of the first remote viewers to “cash in” on their sensational experience were retired U.S. Army Major Ed Dames and retired U.S. Army Captain David Morehouse.

I know some people will disagree, but my take on both Dames and Morehouse is that they were fringy-type guys. Dames was obsessed with his own pet and clumsy theories about UFOs and aliens. He also had a penchant for predicting apocalyptic disasters — none of which have ever come true.

As for Morehouse, his problem was that he really didn’t know all that much about remote viewing. That’s according to his fellow RV Army operative, U.S. Army Major Paul Smith.

Smith wrote a book that described Morehouse as a barely involved slacker when serving with the military RV team, and that Morehouse was practically AWOL for much of his stint with the program as it was operational. Morehouse also engaged in a disastrous affair and suffered a nervous breakdown during his time with the RV team. He almost faced a court-martial, but his problems had nothing to do with remote viewing.

Yet, in his post-military career, Morehouse wasted no time writing a book and boldly billing himself as nothing less than a “Psychic Warrior.”

However, Paul Smith, his 2005 book, Reading the Enemy’s Mind, described Dames and Morehouse as outright liars and frauds in some respects. It was not helpful (in my view) that the high profiles of Ed Dames and David Morehouse in the early post-RV government program years provided fuel for close-minded skeptics to bash remote viewing as woo-woo nonsense and the oeuvre of charlatans.

Fast forward a few years and the serious, credentialed and scientifically grounded remote viewers began coming forth with their own books. Some of the most notable are:

–> Limitless Mind by Russell Targ (see my REVIEW)

–> Mind Trek by Joe McMoneagle

–> Captain of My Ship, Master of my Soul by Fred “Skip” Atwater (see my REVIEW)

–> Opening to the Infinite by Steven Schwartz

–> Reading the Enemy’s Mind by Paul Smith (see my REVIEW)

–> The Seventh Sense by Lyn Buchanon

–> CRV: Controlled Remote Viewing by Daz Smith

And a few more.

After I read all these books and others — and then thanks to the newfangled internet that came along in the 90s — I was able to learn more and get a greater overall understanding of remote viewing. Among the best online resources I found was that provided by the noted sociologist Dr. Simeon Hein. He offered a lot of remote viewing instruction for free, such as this first lesson STARTING HERE.

There are other online offerings of remote viewing info and instruction of varying quality.

Itis interesting to note that the very first manual on “how to remote view” that was created by the classified government program was made available free of charge online as a public domain document.

Now get this:

Even though the RV instruction manual was created inside a top-secret project, the manual itself was never classified! The original authorship and copyright were credited to Ingo Swann, “The Father of Remote Viewing.”

Swann declined to accept or enforce his solid legal claim to copyright, however, saying it “didn’t rightfully belong” to him, and that it was the product of the contribution of many people. That means, as a government-created document, it automatically fell into the sphere of public domain and is free to all.

It’s called The CRV Manual — the Controlled Remote Viewing Manual. You can get your free online and/or printable PDF copy here: CRV MANUAL.

It provides complete instructions that anyone can peruse to study and learn how to remote view. I was surprised to discover that the CRV Manual began to circulate as a free document in the public domain as far back as 1989 — again, before the RV program itself was declassified in 1995!

I don’t know how that works, but I’ll just leave it there.

BELIEVER TO KNOWER

After absorbing volumes of information, including studying the original CRV Manual, I became a believer. I was convinced that remote viewing was a “real thing” and legitimate. It is a natural aspect of human potential, something that we all possess and that we can develop further.

But being “a believer” is different from being “a knower.”

I wanted to be the latter. That meant attempting to take up the formal remote viewing protocols, applying them and taking what the SRI researchers called an “innate human ability” out for a spin.

I reasoned that if I could successfully describe targets using strict “double or triple-blind” protocols, then I could be sure remote viewing was “real” –- and that the smug armies of persistent skeptics were wrong.

Sadly, for me, things did not go so well at first.

I scoured the government CRV Manual line by line and did my best to apply the methodology as it was laid out, step by step. But there were all kinds of problems. For example, the original remote viewers worked in two-person teams. One person acted as a monitor and the other player was the guy or gal in the actual remote viewer seat.

The job of the monitor is to assist the remote viewer during the session.

The monitor provides the target coordinate, observes the viewer to ensure he or she “stays within the proper structure,” records relevant session data, gives feedback when it seems appropriate and provides objective analytic support when necessary.

The monitor role requires considerable skill and training. For example, they must:

- Not ask leading or “queuing questions.”

- Not ask questions in which an answer is implicit in the question.

On the other hand, the monitor must be:

- Pleasant

- Affable

- Nonjudgmental

- Good at asking questions that invoke only non-analytical sense impressions.

Furthermore, RV pioneer developer and futurist Steven A. Schwartz (who did not work on the secret government project but was ahead of them in many ways with his Mobius project) said the monitor position is designed to create a kind of “bio-circuit” with the remote viewer. He said the monitor and the viewer “are both active in producing the final result.”

That means the expectation and the attitude of the monitor will have a significant effect on the RV target outcome.

In short — there was no way in hell that I was going to work with a monitor — even if I was able to find someone who could study up on remote viewing and fulfill this role in the correct manner. That was impossible in my situation. I had no such person at my disposal here in my lonely corner of remote, rural northern Minnesota.

Nevertheless, I forged ahead, working alone, as I applied the CRV protocols as faithfully as possible.

To make a long story short, I found this process was so painfully stripped of warmth & humanity and outright boring that I soon determined that I would rather do just about anything else — such as clean my oven or do my taxes — than practice disciplined, by-the-book CRV remote viewing.

But I still had an urgent “need to know.”

What resolved the problem for me was something I heard one of the leading developers of CRV remote viewing say. Russell Targ was a principal member of the Pentagon-backed RV development team working alongside Dr. Hal Putoff and Ingo Swann. They worked out of SRI — the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, California.

Targ said:

“The secret to remote viewing is that there is no secret. All it requires is getting one’s mind into a relaxed state and then letting the information come to you. That’s it.”

Added to this, another “father of remote viewing” — the above-mentioned Steven A. Schwartz — said:

“The viewer must learn to surrender sense analysis and simply report sense impressions.”

Schwartz added:

“You can train in remote viewing, but it is not like training for a technical skill, an instrument or a language. The key, in my view, to remote viewing and any nonlocal task is the ability to attain and sustain intentioned focused awareness. Study after study has shown that meditators do better than non-meditators at remote viewing.” (Source)

Schwartz said that even experienced meditators must still:

- Learn the protocols

- Learn what the task is about

- Learn to surrender analysis

… but that the central key to training to produce better remote viewing is to learn to meditate and excel at the ability to “attain and sustain intentioned focused awareness.”

MEDITATION TO THE RESCUE

In my view, the comments of those two RV pioneering giants — Russell Targ and Steven Schwartz — gave me the “permission” I needed to practice this art on my own terms.

Better yet, I really had something going for my effort. As it happens, at the time I launched my RV effort, I had been a daily practitioner of Zen meditation for 40 years.

My first instruction in Zen meditation came about in 1981 when I was a student at Winona State University. As part of the curriculum, students are required to complete two courses of 1 credit each in things like bowling, canoeing, ballroom dance or some such other “socially rounding out” activities.

I took bowling and canoeing, but after I flunked bowling class (yes, I really did flunk bowling), I was obliged to make up the credit. Zen meditation for 1 credit was available so I enrolled.

I learned a very formal and disciplined form of Japanese Zen meditation from a philosophy professor who learned meditation in the mountains of Japan. This instruction included a marvelous walking form of meditation. After completing the six-week course in the spring of 1981, I have meditated every day for the past 42 years.

Fortunately, achieving enlightenment was not required to complete the Zen meditation class at Winona State University. So, I passed.

FIRST SUCCESS

Now I was ready to “remote view” in my own way. By the way, I like the term Steven Schwartz prefers over remote viewing — “nonlocal sensing.”

So, I guess I was prepared for my first “nonlocal sensing” experiment.

Here is what I did:

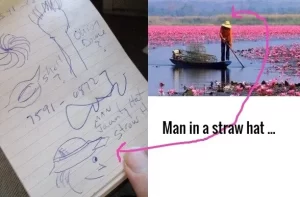

When my wife went to her office for work, I asked her to find some object, photo or anything else lying around her workspace and “select” that as a target. I told her to assign it a random 6-digit number and email that number to me. Send nothing else in the email except the number.

I told her that I would identify the target using only those numbers. The number she emailed to me was 393146.

Here is the result:

Ha, ha! You should have seen the look on my wife’s face when she got home from work and showed me the picture she had selected for a target!

Knowing well my level of artistic skill (or non-skill), I think she fully expected to see some lame drawing of a stick man standing next to a stick cat. But as you can see — and I wonder if you will agree — I came pretty close.

Notice that I wrote the words “white, blue, blue pastel” in the upper left of my sketch. They match the colors of the photo — so that clinched it for me that I had done more than achieved a random match. Note that when I made my sketch, I had no sense that I had done anything other than scribble something randomly on a piece of paper.

I found remote viewing to be a tedious, frustrating VERY NON-MYSTICAL experience!

For me, remote viewing is like just doodling something — anything, randomly — while my mind (or non-mind) is off in a theta state, not thinking of anything but merely experiencing the “no thought” awareness I had learned to culture with Zen meditation.

My next attempt involved going to one of those internet RV sites where you can select random unseen pictures that are matched with target numbers. You work the number and then go back later to open the picture to judge your success.

Here is the result of my second attempt:

Notice that the objects I sketched at the top of the page seem random at first, but I contend that I was sensing the many aquatic plants that are also in the target photo. Note that one of the objects is a “shell” as in a lake or seashell.

So, again, I think I did alright.

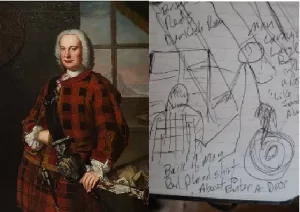

Now here is another example:

Yes, there would appear to be a lot of extraneous “noise” in my sketch, but I do seem to have picked up on at least the central theme of a man in a checked or plaid shirt of sorts. True, I did not get everything correct, such as stating in my notes: “back of a man about to enter a door.”

Whatever the case, this example was enough to convince me that I was doing something right.

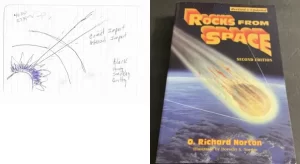

I HIT A TARGET BEFORE IT IS SELECTED

My next example, presented below, is another target selected by my wife. What’s interesting to note here is that I completed my remote viewing BEFORE she selected the target.

In other words, I was blind to the target and my wife was also blind to the target. So, this is (I think) an example of a “double-blind” protocol.

It happened this way: Once again, I told my wife to again select some object or image at her office once she arrived at work and to email me only a number. However, instead of choosing something from her office, my wife sent me a number right away in the morning — but she had not yet selected a target.

She waited until after work to do that. On her way home, she stopped at the public library and chose a book from the shelf. That was to be my target.

When she got home, I showed her the sketch I had done earlier that afternoon — again, hours before the target had been selected. She pulled this book out of her tote.

SOME TOTAL MISSES TOO

In all, I attempted about 30 targets before ending my experiments with remote viewing or nonlinear sensing. Yes, some of my drawings were absolute misses, such as when I drew a “spaceship” and the target picture turned out to be a cottage in the Irish countryside.

About 20 of the targets I worked on are of similar quality to those which I have presented in this article. Five or six were complete flops and the remaining few seemed to be “partial hits.”

Once I had proven to myself that remote viewing was “real” and converted myself from “believer” to “knower,” I put the subject aside so that I could move on with the many other consciousness exploration projects on my docket.

Yes, yes, I know. My sampling is way too small to satisfy scientific rigor and proper statistical analysis.

Whatever the case, I had seen enough — and directly experienced enough. Knowing that remote viewing is a legitimate tool that I could now pick up at any time to use — for whatever purpose — made my efforts well worth the time.

I know this skill will come in handy in the future.

NOTE: For more stories about DYI consciousness exploration, please see: KEN-ON-MEDIUM