By KEN KORCZAK

The autobiographical story of rural Ohio resident and amateur astronomer extraordinaire, Leslie Peltier, is a classic book for the ages

Let’s just call this book what it is: A rare masterpiece.

Starlight Nights was never destined to be a best-seller, but it enjoys permanent cult status among a significant audience of sensitive people who love the stars, love nature — and perhaps a certain segment of society who will pine forever for a slice of American rural life that is now mostly lost.

It is not over-the-top to say that people may find reading Leslie C. Peltier’s ode to the starry heavens a religious experience — or better yet, a mystical experience.

This book, published in 1965, has a profound effect on those attuned to a nuanced mode of existence — those who can appreciate the incredible beauty in something as small as a wildflower, a moth, a fairy shrimp — or as grand as a night sky paved with glittering stars.

Starlight Nights is the autobiographical story of a guy born on the second day of a new century, 1900, on a 50-acre farm outside the small town of Delphos, Ohio.

Early on, Leslie C. Peltier developed a love affair with stars and telescopes. He gets zapped as a boy with the spectacular appearance of a stunning comet, known only as 1910-A1 because it was the first comet discovered in 1910.

As it turns out, 1910 was also the year of the once-every-75-year appearance of Halley’s Comet, but Comet 1910-A1 stole Halley’s thunder! The former was so bright it could be seen during the daylight hours and easily outshone the Planet Venus.

Years later, many old-timers who recalled the splendor of Hally’s Comet were almost certainly remembering Comet 1910-A1. Halley’s was a dull anti-climax by comparison — as it was when I observed its return in 1985.

But Peltier describes an earlier transformative event that triggered his lifelong pursuit of amateur astronomy. It happened when he was just five years old. Looking out the window of his rural farmhouse one evening, he was transfixed by a sighting of the Pleiades (sometimes called the Seven Sisters).

Remember, these were the days before every farm had a yard light or indoor electric lights, and before the light pollution of surrounding cities began to blot out the beauty of starlight. The jewels of the Pleiades open cluster presented a mesmerizing sight and sparked the imagination of a child.

It began a lifelong journey of amateur astronomy — and no one did it like Leslie Peltier. He transformed stargazing into an art form, a lifestyle and a gentle philosophy that urged humankind to walk lightly and reverently among the natural world.

THE STRAWBERRY SPYGLASS

To earn money for his first telescope, Peltier got a job picking strawberries. He filled 900 quart-sized containers at 2 cents per quart. That brought the $18 he needed to purchase via mail-order a small, non-astronomical telescope with a 2-inch aperture.

He dubbed this “the Strawberry Spyglass.” It was an instrument of profound beauty. It was of French manufacture and sported a heavy collapsible brass housing encased in black pebble leather. Because it was for terrestrial use, images appeared right-side up.

Astronomical instruments eliminate the erecting lens to allow more precious starlight to flow through — one less lens to absorb photons — and thus, they show images upside down. Peltier’s new telescope came with two interchangeable oculars (eyepieces) of 30X and 60X magnification power. It also had a solar filter.

Later, after Peltier obtained his first astronomical telescope, he had to adjust to seeing star fields with which he was familiar now appearing “upside down,” so to speak. However, Peltier was able to accomplish more with his humble 2-inch “spyglass” than most other amateurs did with bona fide astronomical instruments.

He soon began using the Strawberry Spyglass to make variable star observations for an organization called AAVSO — the Association of Variable Star Observers. He would go on to make an incredible 132,000 variable star observations as he reported his data to AAVSO for more than 50 years. (One source pegs his tally at 180,000).

Professional astronomers around the world were eager to have this critical celestial data generated by amateurs. It was a way for backyard stargazers to contribute to “real science” as they pursued their hobbies. In effect, variable star data generation was like an early form of crowdsourcing.

In fact, it was Peltier’s dogged dedication to variable star observation that landed him his next telescope — a marvelous Mogey refractor with a 4-inch objective lens. It was bequeathed upon him as a “loan” (which turned out to be permanent) from AAVSO.

The value of that telescope in today’s money would be about $21,000.

But that was only the beginning. Peltier’s ongoing contributions to observational astronomy landed him another “gift” a few years later, another telescope “loan,” this time from Princeton University. It was a fabulous Fitz Comet Seeker with a 6-inch refracting objective lens. It had a short F/8 focal length that provided a wide field of view making this instrument ideal for comet hunting.

The Fitz Comet seeker was also an implement of sublime pulchritude. Its tube was fashioned from the redolent richness of polished brown mahogany and its fittings were of gleaming brass. Peltier put the Fitz Comet Seeker to excellent use. He discovered nothing less than 12 comets over his career, a remarkable achievement for a solitary amateur astronomer working alone out in a cow pasture.

His fourth comet, discovered in 1936 (with the 4-inch Mogey), was honored with his name — Comet Peltier. It became a naked-eye object, although just barely, reaching only slightly higher than 6th magnitude, the lowest measure of star brightness that can be seen by the unaided eye.

A second visible comet would also bear his name. This brought him considerable national recognition. The discovery of new comets was a much bigger deal through the first 3/4 of the 20th Century than it is today.

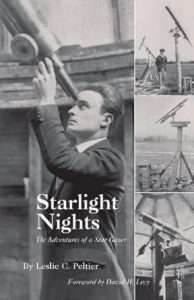

He also gained world notice for the special kind of observatory he built for the Comet Seeker — his famous Merry-Go-Round observatory. Below is the only Public Domain image I can find — but I urge readers to check out a fantastic schematic of this invention here: Merry-Go-Round.

This unit could fully rotate at the turn of a steering wheel (salvaged from an old car) inside. Peltier sat comfortably at the center on a repurposed automobile seat. The observatory design is remarkably ingenious and leveraged various wheels and pullies scavenged from scraps of old machinery. This enabled Peltier to effortlessly rotate around and scan the entire dome of night quickly and efficiently using the powerful 6-inch Fritz.

No wonder he bagged 12 comets!

In addition to comets, Peltier pulled off the fantastic feat of discovering four exploding stars, or what astronomers call a nova or supernova in the case of really big ones. Four novae discoveries by a single amateur astronomer is an astounding achievement.

In addition to publishing three books, Starlight Nights, The Place on Jennings Creek and Guidepost to the Stars, Peltier sold an occasional article to astronomy publications and nature magazines. All this from a man who left high school after 10th grade to work on the farm. The latter was necessary because his older brother was drafted to serve in World War I. Peltier was a self-taught writer, astronomer and naturalist.

He eventually came to be known as, “the world’s greatest amateur astronomer” — the title designated upon him by the renowned astronomer Harlow Shapley, director of the Harvard College Observatory.

Peltier died at age 80 in 1980. He passed suddenly from an apparent heart attack outside between the two things he loved the most — his telescope observatory and one of his gardens.

A BOOK THAT CHANGED MY LIFE

I purchased Starlight Nights more than 50 years ago when I was 11 years old. I found it in a large cardboard box of random used books that were being sold in the corner of a clothing store.

While I waited for my mother to shop, I mined through the book bin and grabbed Starlight Nights — it was 50 cents. Wow! I still marvel to think about it! I didn’t know it yet, but 50 cents and a secondhand book were about to change my life forever!

When I stumbled upon Starlight Nights at age 11, I had already been a dedicated amateur astronomer for several years. I plied the heavens with my beloved 6-inch Newtonian reflector — a Cave Astrola — manufactured by the Cave Optical Company of Long Beach, California.

During the past five decades, I have re-read Starlight Nights countless times. Of the thousands of titles I have read over the years, I can’t think of one that has affected me more profoundly than this rare jewel in the starry pantheon of astronomical literature.

NOTE: For more stories about amateur astronomy, please see: KEN-ON-MEDIUM