By KEN KORCZAK

By KEN KORCZAK

It takes a genius to catch a genius. The British Crown tapped the smartest man in the world to catch a criminal mastermind

Hey, remember that ridiculous movie a few years ago that rebranded President Abraham Lincoln as a vampire slayer? Or how about the Star Trek feature film wherein the plot revealed that William Shakespeare was actually a Klingon? Then there was the spinning of Jane Austin’s Pride Prejudice as a zombie apocalypse movie.

They’re called movie mashups. Highly creative and wacky, they nevertheless represent creative leaps that may entertain — or not so much. Now imagine you were pitching this mashup movie script to a Hollywood producer:

The brilliant Sir Isaac Newton takes on the role of a super crime fighter. The genius, mathematician and astronomer is transformed into a combination of Sherlock Holmes and Elliott Ness as he takes on a dangerous London criminal mastermind.

Well, if I were a Hollywood producer I would green light this plot ASAP. Why?

Because this is a mashup that happens to be absolutely true!

It really happened!

In bona fide historical events worthy of a Tinsel Town flick, the smartest man in the world was thrust by British authorities into the thick of what was an ongoing crime spree of the century across London. The government was desperate. In dire need of a solution, The Powers That Be opted to pin their hopes on Sir Isaac. They were betting he could match wits — and outwit — one of London’s most determined and clever illicit operatives.

That criminal was William Chaloner. To say that Chaloner was engaging in the crime of the century is not an exaggeration. His actions could have brought the British economic system to its knees.

That’s because Chaloner was a counterfeiter — but he wasn’t just any two-bit coin faker. He was an unrelenting, persistent and prolific producer of gobs of phony money that was flooding the streets of London and eroding the integrity of the nation’s legal tender.

THE ORIGINS OF A MASTER BUNKO ARTIST

Chaloner started out small. He broke his teeth as a grifter by producing Birmingham Groats (worth about the equivalent of four cents). When this proved a handy way to gain wealth, Chaloner moved on to the big leagues by manufacturing guineas, French pistoles, crowns, half-crowns, banknotes — and he even found a profitable trade in printing bogus lottery tickets.

Born into poverty in rural Warwickshire in 1650, Chaloner was apprenticed into the depressingly mundane trade of nail making. It wasn’t long before he opted out and made his escape to England’s largest city. There he hoped to find excitement and attractive opportunities.

He started out as a maker of fake watches. This was legal. It was common for people to purchase real-looking but phony pocket watches that could be worn on a chain as a sign of prestige and status. A fake watch could be had for just pennies on the pound.

Of course, Chaloner could never leave well enough alone. He upped the value of his faux watches by — and stay with me here — combining them with an appendage that could be used as a dildo!

That’s right!

If you’re having difficulty picturing a pocket watch that somehow incorporates a functional dildo attachment, well then, you’re like me. So, let’s just put this fascinating tidbit aside and move on with the main thrust (no pun intended) of our story. Chaloner ascended to his criminal career of counterfeiting at a time when the state of English currency was in disarray.

The problem was multifaceted, but three factors stand out:

-> Hard-struck silver coins were being clipped around the edges. People did this to keep a little silver before they spent a coin. After a while, they could melt down their clippings into bullion and sell it.

-> Silver bullion in Paris and Amsterdam had greater face value than it did in London. Thus, melted down clipping or whole coins could be shipped abroad for an incredibly significant profit.

-> The third and most severe problem was rampant counterfeiting of British coinage. Brilliant metal-working and die-casting technicians like Chaloner made counterfeit molds and die-stamped their faux coins with expert counterfeit images.

By 1669, 10% of all British coinage was fake. That would be enough to wreak havoc on the monetary system of any sovereign nation.

William Chaloner was like the Al Capone of counterfeiting. He flooded the market with bogus money through an extensive web of handlers, petty criminals and prostitutes. He commanded captains and lieutenants — but these were dangerous and uneasy alliances. Counterfeiting was a scummy business with no honor among thieves. Betrayal, backstabbing and ratting out an accomplice to save one’s own skin was standard practice.

Even so, Chaloner kept things together with another kind of silver — his silver tongue. He was noted for his truly remarkable eloquence and ability to talk his way into or out of any thorny situation. He could fool cops, bamboozle authorities, outwit lawyers and confound his fellow criminals with his brilliant gift for rhetoric.

Chaloner possessed what the Londoners of the time called “the best knack of tongue-pudding.”

He was also begrudgingly hailed as a brilliant practitioner of his art — building forges, stamps and dies that were veritable works of art. Writing in 1946, Sir John Craig wrote in his book, Newton and the Mint:

“Chaloner was the most accomplished counterfeiter in the kingdom, …. so nice an artist of dies that it galled him to spoil their perfection by use.”

To catch a brilliant criminal, British authorities knew what they needed:

A GENIUS TO CATCH A GENIUS

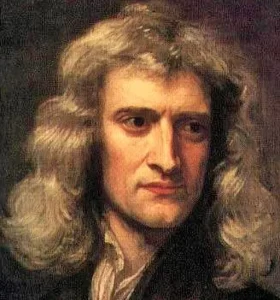

For that, they went to the loftiest pinnacle of intellect. Secretary of the Treasury Sir William Lowndes tapped none other than Sir Isaac Newton — whom astronomer Carl Sagan called the “the most intelligent human being ever to live” — to take on the monumental problem of solving the Crown’s currency crisis.

Among the highest priorities tasked to Newton was tracking down and squashing that London cockroach who was William Chaloner.

Newton was charged with building an airtight case against the devilishly clever fabricator. The Department of the Treasury wanted Newton to do whatever it took to get Chaloner off the streets and land his boots onto the rough-hewn boards of a gallows — where he could be hanged.

Newton thereby received appointment as Warden of the Royal Mint in 1696.

Seated in his new position of power, Isaac Newton wasted no time putting together an intricate web of informants, spies, special operatives and government agents to go after Chaloner. He was able to compile a massive body of evidence composed of written statements, confessions and detailed reports on all the financial forger’s activities.

Now consider this amazing fact:

Sir Isaac Newton himself, the refined and exultant gentleman, dressed down in shabby attire to appear like any common sod. He did so to visit seedy taverns and pubs frequented by the dangerous criminal scum of London. He sniffed out the favorite hangouts of those who trucked in counterfeit swindling and printing bogus lottery tickets. Putting himself in considerable peril, Newton took a hands-on and on-the-streets approach to gathering information and seeking connections that could lead to his quarry.

Newton’s goal was to build an insurmountable case against the slippery silver-tongued devil — an operator who had proved time and again he could weasel his way out of tight spots and deflect blame and guilt toward others.

One of Chaloner’s primary MOs was convincing his minions to do the dangerous and dirty work for him. He was a master of setting up situations of “plausible deniability” for himself. Chaloner knew how to put a critical distance between himself and the actual deeds of wrongdoing. If his lackeys got pinched, imprisoned or hanged — well, that was nothing to him.

Unfortunately for Chaloner, he was now matching wits with the man who invented calculus, wrote the Mathematica Principia, developed the inverse square law and revolutionized physics. Heck, he invented classical physics!

Sooner or later, Chaloner was bound to slip up. When that happened, Newton would be ready to pounce.

That misstep came in 1698. Chaloner had just completed engraving a set of copper plates for printing phony lottery tickets. He hid the plates between printing runs. He was betrayed by a slimy “coiner” associate by the name of David Davis. Davis was arrested on another charge and without hesitation ratted Chaloner to an undersecretary of the Secretary of State Charles Talbot, the 1st Duke of Shrewsbury.

That misstep came in 1698. Chaloner had just completed engraving a set of copper plates for printing phony lottery tickets. He hid the plates between printing runs. He was betrayed by a slimy “coiner” associate by the name of David Davis. Davis was arrested on another charge and without hesitation ratted Chaloner to an undersecretary of the Secretary of State Charles Talbot, the 1st Duke of Shrewsbury.

Davis’s testimony was enough to get Chaloner arrested and hauled off to the dismal environs of Newgate Prison.

Newton understood that Chaloner would pull every trick out of his hat to survive his trial. For example, he could bribe powerful people and blackmail others. Thus, Newton relentlessly continued to gather evidence and build a case as the trial date approached. He never let up.

When Chaloner’s day in court finally arrived, Newton’s court representatives laid out a devastating mountain of evidence — it was a brilliant array of facts and information assembled by the author of the theory of gravity himself.

The jury took just minutes to come back with a verdict: Guilty!

Chaloner was sentenced to be hanged on March 22, 1699. He was 49 years old. He had enough time to make some last-ditch efforts to save his neck. That included writing a letter directly to his nemesis, Isaac Newton. It read, in part:

“Dear Sir, do this merciful deed… for God’s sake, if not mine, keep me from being murdered. Dear Sir, nobody can save me but you. O my God, I shall be murdered unless you save me. I hope God will move your heart with mercy and pity to do this thing for me.

I am Your near murdered humble servant, Wm Chaloner.”

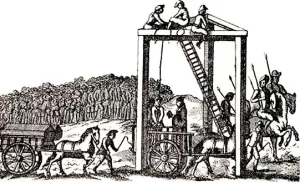

Newton ignored the plea, of course. Chaloner was hung on the Tyburn Gallows with an appreciative audience in attendance. Sir Isaac was not one of them. According to witnesses:

The executioner’s men pulled the ladder out of the way and Chaloner dangled, twitching and jumping (the “hangman’s dance”) as long as it took –- minutes, at least — for life to choke out of him. Richer men often paid the hangman to pull on their legs to speed death. Not the destitute Chaloner.

After taking down Chaloner, Newton turned his attention to the many other grave challenges that plagued the English monetary system. He held his position at the Mint for some 30 years and was eventually appointed Master of the Mint. Newton’s actions in righting what was wrong with British money staved off disaster for his country— but that’s another story.

Note: For more stories of unusual history, please see: KEN-ON-MEDIUM