By KEN KORCZAK

By KEN KORCZAK

Part 1: There is No Spoon … Um, I Mean Music

Part 2: Mescalito Riding His White Horse. Author Mike Fiorito’s new book inspired by the adventures of musician Peter Rowan

Four decades ago, when I was a general assignment reporter at a Minnesota daily newspaper, a stout, 40-something bald guy with a scruffy, no-mustache beard and a ridiculously ill-fitting suit strolled into the newsroom to hand me a press release.

His name was Jerry Barney.

I doubled as the “farm editor” for our paper. That’s why Jerry Barney marched straight over to my desk with his information. He worked as a communications guy for an influential agricultural policy lobbying organization.

Jerry and I naturally engaged in some chit-chat. He was a former newspaper reporter, so we had something in common. One day he casually mentioned that he would be performing at a bluegrass festival out by one of the 10,000 heavenly sky-blue lakes of northern Minnesota. He told me that playing bluegrass was his passion. I suddenly understood why he looked so awkward in the typical business suit of a lobbying firm.

Then Jerry fired a tiny dart into my brain: He said it was not unusual for his group to “play bluegrass music for 24, sometimes 36 hours straight, without a rest.” He added a quip that made me laugh. He said: “After one of those marathon sessions, I crawl back to my van and pass out for a while.”

“I’ll bet!” I said, feeling instant respect for this guy — although I knew nothing about bluegrass music and, full disclosure, I never listen to any music at all of any kind.

That is because I may (or may not be) affected by what neurologists call musical anhedonia which presents in 3% to 5% of the population. Like most people with musical anhedonia, I can recognize and understand music, I just don’t derive pleasure from it. This “effect” (it’s not necessarily considered a “dysfunction” or “condition”) was first formally identified in 2011.

For me, however, I’m certain it began when I was eight years old. One summer day, I was looking up into a blue sky, and I began to see a series of bizarre flashing lights. Shortly thereafter, I experienced what I know today as a petit mal seizure followed by a severe migraine. This a type of epileptic seizure that does not involve convulsions, but rather, a short period of what I’ll describe as “weird and wavery disassociation.” My brother has full-blown epilepsy with grand mal seizures, so it’s a “genetic thing” in my family.

Two other conditions soon manifested themselves out of my new (and now lifelong) petit mal seizure condition. One is commonly called Alice in Wonderland Syndrome or what the medical literature calls Dysmetropsia micropsia and/or Dysmetropsia macropsia.

Dysmetropsia micropsia is when everything in one’s field of vision suddenly begins to look tiny as if looking through the wrong end of a telescope. Dysmetropsia macropsia is when everything is magnified to a ridiculous degree, making everything look “giant.” This experience can last from a few seconds to maybe as long as 20 minutes.

Lewis Caroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, was known to suffer from epilepsy and severe migraines. It is speculated that these produced bouts of Dysmetropsia micropsia and macropsia for Caroll and thus inspired the experiences of Alice in his tale.

The other outcome for me may have been musical anhedonia. I hasten to preempt any reader from thinking “Oh my! How awful that must be! No music?” However, there is no problem.

Even though I vividly remember enjoying music from ages zero to 8, my inability to appreciate music thereafter is no big thing. When others have asked me about it over the years, my reply is always the same: “I can say that I have never given it a thought.” Consider people born without hearing. They go through life without ever hearing music, bird song or the voices of their loved ones, and they still lead full, imaginative and happy lives.

NOW BACK TO JERRY BARNEY

As it happens, I was also under pressure at the time I met Jerry to drum up a story for a quarterly magazine my newspaper’s company also published regionally in Minnesota. It was called Country Life. When Jerry told me he played bluegrass, my young reporter’s “story radar” blipped. I asked Jerry if I could do an article about his alt-life as a bluegrass musician. He readily agreed.

The result was a cover story for Country Life titled:

“Jerry Barney is a Bluegrass Bum”

That headline was inspired by Jerry, who referred to himself during our interview as “just a bluegrass bum at heart.” The story was well received, and Jerry kindly told me he liked it. We remained friends after that. That’s why I decided one weekend to go check out a nearby bluegrass festival in which Jerry said he would be playing “probably all night.”

The reason “Jerry’s dart” — the prospect of an all-night bluegrass session — intrigued me is that I was familiar with the concept of music as a tool to induce a trance state when played continuously over long periods At this point in my life, I had been practicing a formal, acetic form of Zen meditation for about five years, and I had also read the works of Rumi and studied Sufism.

A Sufi ceremony called “Sama” includes something called “Dhikr.” The latter involves singing, playing instruments, dancing, recitation of poetry and prayers. All of this can induce a trance state and catapult the practitioner to a higher state of consciousness. The Whirling Dervishes of Istanbul are the most famous examples of Sama and Dhikr.

But I had also read about the San people of southern Africa’s Kalahari Desert. I was made aware of them after viewing the popular 1980 movie, The Gods Must be Crazy. As it happens, the San also use a combination of music and ritual dance which they perform nonstop for hours to induce a trance state.

Now get this:

Years later, Dave Matthews of the Dave Matthews Band visited the San people in southern Africa. Matthews was deeply moved by their music. He asked his guide: “What are the meanings of the words they are singing?” His San guide answered:

“There are no words to these songs … because these songs … we’ve been singing since before people had words.”

Stick a pin in that because it will be relevant to my discussion in the Part 2 of this article about Mike Fiorito’s book and his series of interviews with the legendary bluegrass icon Peter Rowan.

BLUEGRASS MARATHON

Anyway, the day of the bluegrass festival arrived. I went out to the park by the lake where a multitude of people were gathered to enjoy nonstop bluegrass entertainment. I set up a lawn chair and brought a book. My goal was to stay as long as I could — possibly all night — not to listen to the music, but because, I confess, I wanted to look for possible signs of San-like or Sufi-like trance effects in the players and maybe even the concert attendees.

I was thrilled to see my friend Jerry Barney on the stage, alternately playing the autoharp, standup bass, and guitar as well as singing. I was delighted and felt special when Jerry noticed me and winked at me from his musical platform as I sat alone on my lawn chair with a book.

Incidentally, I remember what I was reading: It was the 1981 book Critical Path by the American genius R. Buckminster Fuller. As the music flowed past me — skirting my neurodivergent brain by a mile — I recall how disturbed I was when Bucky wrote about why the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan in 1979, and how if the Russians prevailed, they would proceed to sweep through Iran and gain access to the Indian Ocean and thereby gain control of Middle East oil and deal a decisive blow to the West in the Cold War.

Incidentally, I remember what I was reading: It was the 1981 book Critical Path by the American genius R. Buckminster Fuller. As the music flowed past me — skirting my neurodivergent brain by a mile — I recall how disturbed I was when Bucky wrote about why the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan in 1979, and how if the Russians prevailed, they would proceed to sweep through Iran and gain access to the Indian Ocean and thereby gain control of Middle East oil and deal a decisive blow to the West in the Cold War.

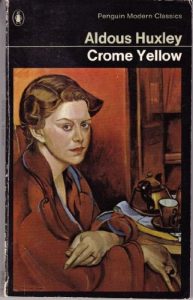

I was so bummed by Fuller’s prediction of Soviet geopolitical dominance, I put the book down and walked back to my old friend, Pulchritude, who was waiting patiently for me in the parking area. Pulchritude was my beloved & battered midnight blue ’66 Chevy pick-up truck with a manual “3-on-the-tree” shift! Inside her cab, I usually kept about two dozen moldering books behind the bench seat which could pitch forward. I rummaged through my “pick-up truck library” and selected the title Chrome Yellow. This was Aldous Huxley’s first novel published in 1921.

I sauntered back to my chair, navigating the throngs of bluegrass enthusiasts — their campfires, beer, fringy denim, cookout grills, black worn-leather hats — and settled in to read. The din of the concert attendees and the music went silent as I became absorbed in Chrome Yellow.

I sauntered back to my chair, navigating the throngs of bluegrass enthusiasts — their campfires, beer, fringy denim, cookout grills, black worn-leather hats — and settled in to read. The din of the concert attendees and the music went silent as I became absorbed in Chrome Yellow.

When I finished the last page, I looked up and it seemed like there had been missing time. I checked my watch, and it was now after 1 a.m. Up on the stage, Jerry Barney and his cohorts were ardently picking strings, singing, seamlessly executing chord changes and whatnot. I thought: “Wow, these folks have been playing for at least 8 hours nonstop, and it’s still hours until sunrise!”

My next thought was: “Wow, so Huxley had already worked out the core themes in Chrome Yellow that would underpin the central elements of Brave New World published 10 years later in 1931!”

I then scanned for signs among the band and the crowd for any indications of San or Sufi-like trance state. I don’t know what I expected to see. Frankly, I noticed nothing special. But that notion, “nothing special” prompted a memory of a quote from Shunryu Suzuki’s 1970 book, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind:

“If you continue this simple practice every day, you will obtain some wonderful power. Before you attain it, it is something wonderful, but after you attain it, it is nothing special.”

I hung in at the bluegrass fest until maybe about three o’clock and then went home. A few days later, I ran into Jerry Barney. He asked me what I thought of the musical marathon. Instead of giving him a direct answer, I brought up Suzuki’s notion of enlightenment. I said:

“Jerry, let me ask you something. A Zen master said that before one achieves enlightenment it seems like it is something special, but after one attains it, it is nothing special. Is that what bluegrass is like for you?”

After some thought, Jerry replied:

“I’ll tell you what. At the end of one of those marathon sessions, I always run over and jump into the icy cold water of a Minnesota lake. After the immersion in the music and the water, I feel washed clean.”

Jerry was an ardent Christian, and I took his “washed clean” to be influenced primarily by that spiritual tradition — but it struck me that “washed clean” might be another way to describe the Buddhist “Sunyata” (Emptiness).

After I left the newspaper and moved away for other pursuits in 1987, I lost track of Jerry Barney. He died in 2019 at the age of 81. His obituary notes that Jerry was widely regarded as a “Bluegrass legend” in the Upper Midwest, and that he penned more than 600 songs. Some of the “big names” who recorded his music include Porter Wagoner, Lefty Frizzel, the country duo Lonzo and Oscar and others.

Part 2: MESCALITO RIDING HIS WHITE HORSE

Part 2: MESCALITO RIDING HIS WHITE HORSE

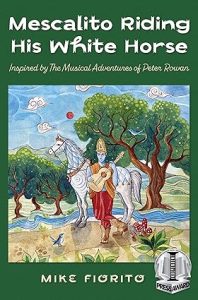

I had not thought about Jerry Barney in many years, but it was reading Mike Fiorito’s sensational book, Mescalito Riding His White Horse, that conjured fond memories of my old bluegrass friend.

The titular “Mescalito” is taken from a song written by bluegrass giant Peter Rowan.

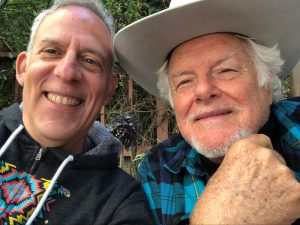

Fiorito, a journalist and writer from The Bronx, had long been an ardent fan of Rowan. Fiorito was thrilled when, almost by happenstance — or more likely a series of synchronistic events — brought an opportunity to meet the man whose music he had idolized for decades.

The result is an epic interview for musical journalism history. But that’s not all! “Mescalito” is more than just another in-depth Rolling Stone-style piece about a legendary figure who is a musical Brahma to millions.

This book reads more like a transcendent travelogue wherein a student meets a spiritual master. It’s Jack Kerouac’s On the Road meets Hermann Hesse’s Damien or Siddhartha — or perhaps Lazy Man’s Guide to Enlightenment by Thaddeus Golas mashed-up with Hammer of the Gods by Stephen Davis.

Mike Fiorito describes his remarkable and intense relationship with a musical artist who played a role in formulating the worldview of a tough, streetwise young man raised in the mazes of the Concrete Jungle — but also a guy attuned to the natural world and an ardent seeker of whatever might be lingering “just beyond the veil.”

It’s as if Mike Fiorito was wandering along the dharma path and then, in the distance, he espies a Great Pandit coming at him from the opposite direction. The two meet with gladness in their hearts and then sit on a roadside rock to converse. In their parley, they discover they are not strangers after all but have known each other for countless millennia and across timeless oceans of Hiranyagarbha, the Vedic term for “manifestation of the cosmos.”

Fiorito reports:

“I’ve always known Peter Rowan. We’ve been crossing paths in the multiverse for billions of years, traversing the mysterious wormhole transportation system, dancing illusion’s dance, singing illusion’s songs.”

Fiorito writes with an unapologetic audacity. I use “audacity” in the way Dr. Martin Luther King selected it for a 1967 speech when he said: “We must walk on in the days ahead with an audacious faith in the future.” King, in turn, was inspired by a sermon of Frederick G. Sampson who said:

“… with her clothes in rags, her body scarred and bruised and bleeding, her harp all but destroyed and with only one string left, she had the audacity to make music and praise God … To take the one string you have left and to have the audacity to hope.”

Peter Rowan strikes me as the kind of guy who would find a way to create music even if he only had a single string made of twisted rawhide strung on a guitar fashioned from a hollowed-out gourd.

Fiorito’s literary brand of audacity is wild, fun and profound as demonstrated when he proclaims nothing less to be the reincarnation of Peter Rowan’s cat! That’s right! Fiorito writes:

“On a few occasions, we’ve made contact. Like the time I was a cat being born in Pete’s backyard in 1947, to help him recall the cycle of life. He was five years old. After seeing the cat being born, wandering around the farmyard near his house, Peter had voices calling him from deep inside the earth, songs of moss and fungi, sung like prayers …”

“… it was the cat that awakened his sense of the cycle of life. And I was that cat.”

Yes! Go for it, Mike Fiorito!

Mescalito Riding His White Horse is strewn with so many glittering gems that I feel inadequate to do justice to the entirety of this book in a single review. More so, I don‘t want to give too much away so that readers can get this book and discover its visceral magic for themselves.

However, I’ll just briefly circle back to that quote told to Dave Matthews by his African San guide:

“There are no words to these songs … because these songs … we’ve been singing since before people had words.”

It’s a notion I suspect Peter Rowan would share. In his conversation with Fiorito, Rowan spoke of something country & bluegrass demiurge Bill Monroe once said to him:

“Pete, when the music is right, you will feel like you’re flying. And then you can hear the ancient tones.”

To that, Peter added:

“It wasn’t you hear the ancient tones and so you go and try to make them. You make the music and the ancient tones emerge. You follow the musical rules, but you are not invested in them. The ancient tones emerge from the application of selflessness. As I said that, I’m thinking of African kora music … it’s the earliest rhythm of human beings …”

Fiorito and Rowan speculate that music itself might be a universal cosmic pathway — the key to unlocking the awakening of all humankind. As audacious as this sounds, it just might be true.

But what about people like me who don’t “hear” music or the deaf? Well, I’ll paraphrase an adage that originates from the Hindu tradition:

“There are a thousand pathways that lead to the top of the mountain. It doesn’t matter which pathway you take, as long as you arrive at the summit.”

ADDITIONAL NOTES:

-> For more about Peter Rowan and his music, check out his YouTube site here: PETER ROWAN

-> Mike Fiorito’s author’s page can be found here: MIKE FIORITO

-> See my review of Mike Fiorito’s book, For All We Know here: FOR ALL WE KNOW: A UFO MANIFESTO

NOTE: For more in-depth book reviews, please see: KEN-ON-MEDIUM